|

An avid collector of insects, Bassett preserved and mounted over six thousand specimens and discovered more than 125 new species of flying insects in the Waterbury area. Bassett specialized in gall flies, insects that cause swelling (galls) in the plants they feed on, and contributed frequently to scientific journals. Near the end of his life, he donated portions of his collection to the American Entomological Society, the American Museum of Natural History, Yale, and Cornell.

Bassett’s writing ventures were not limited to scientific journals. One of his earliest works was a poem, “Lines to the Comet,” inspired by the Great Comet of 1861 and published in the Waterbury American newspaper on August 2 that year. The comet was visible for nearly three months that summer, passing so close to Earth that the planet was actually inside the comet’s tail for two days. In 1889, Bassett published an illustrated history of Waterbury and the city’s leading industrial companies. He was also a contributor to Anderson’s three-volume History of Waterbury, published in 1896.

Although he accomplished many great things for the Silas Bronson Library during his tenure, Bassett tried for decades to discourage library patrons from reading popular fiction. In the library's 1874 Annual Report, Bassett scoffed at popular novels, boasting that “the new books added during the year have been less suited to the tastes of devourers of sensational novels than ever before.” While accepting that works of fiction would continue to be an important part of libraries, Bassett stressed that books “of immoral or purely sensational character” should be omitted from the library shelves. He warned against novels that included “false philosophies” or “fatal religious heresies,” certain that thousands of readers would be unwittingly subjected to the “moral poison” they contained. Bassett would no doubt be horrified by the modern-day popularity of the Harry Potter and Twilight novels.

Further on in the 1874 report, Bassett again railed against the “sensational class of novels,” advising that novel readers will read the “best works” of fiction if the “poor trash” is not available. Bassett’s distaste of popular fiction was not limited to books read by adults. He also complained about objectionable books for children, including the work of Horatio Alger, declaring that “evil results follow their reading, when it is carried to the extent of some of our borrowers” who were reading an entire book every day.

While it may seem incredible that a librarian and former teacher would object to children reading, Bassett went on to declare that children who read one or two fiction books a day gained nothing from their “gluttonous habit,” and that they were even harming themselves by reading so much poor quality fiction: “Among the sad results of such reading—if reading it can be called—are a weakened memory, a distaste for everything that taxes, even in a slight degree, the powers of thought, a confusion of ideas that in some cases is little removed from downright idiocy, and, often, very serious injury to the reader’s health.”

Bassett’s crusade against popular fiction eventually softened. In his 1879 report, he defended the reading of novels as a much-needed escape from the hardships of daily life: “To a large class among us life is too real, and the struggle for existence too earnest to require that it be forever kept in view, and the story that beguiles for a little [while] the overworked from the thought of his toil, or the sick from his pain, becomes… an angel of good.” Bassett held firm, however, in his belief that children should not be allowed to read fiction nonstop, calling such “misuse of books” a “serious evil resulting from our free public library.”

Other challenges during Bassett’s tenure were more physical: the Gentlemen’s Reading Room was frequently “flooded” with tobacco juice and prone to encouraging “loafers and loungers” to “infest” various “skulking places” in the building.

In 1886, Bassett received a letter sign “A Mother” requesting that he do something to stop book borrowers from writing obscene words and pictures inside the books. Difficult book borrowers included families with young children: Bassett complained in 1891 about books being returned with butter smears and sticky jam on the pages. His favorite borrowers were ones who kept the books they borrowed wrapped up with paper and twine when not being read.

Bassett resisted certain changes to library operations, rejecting suggestions to allow people to borrow more than one book at a time, or to let the public access the books directly instead of requiring that a library assistant fetch the book from the shelves, despite a growing demand for these services.

Bassett’s tenure as the city’s Librarian included technological advancements: the library bought its first typewriter in 1882, installed electric lights in 1883, created its first card catalogue in 1884, and adopted the Dewey Decimal system in 1886. The library’s collection expanded during the late 1880s to include collections of coins and stuffed birds. The staffing at the library transitioned from all men to mostly women, with the exception of Bassett, during the 1880s.

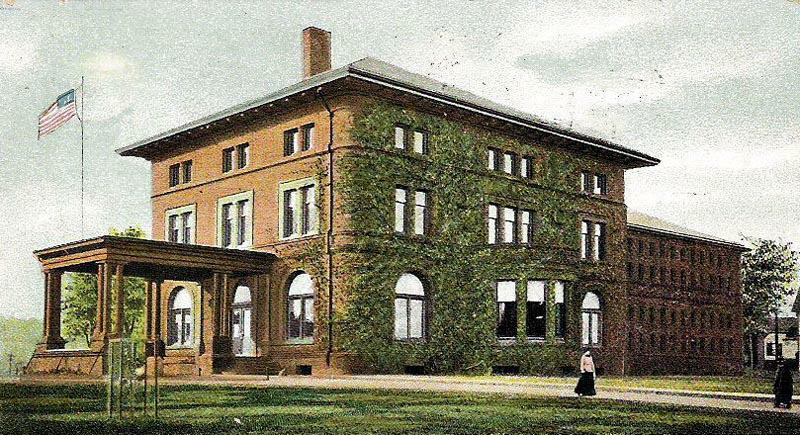

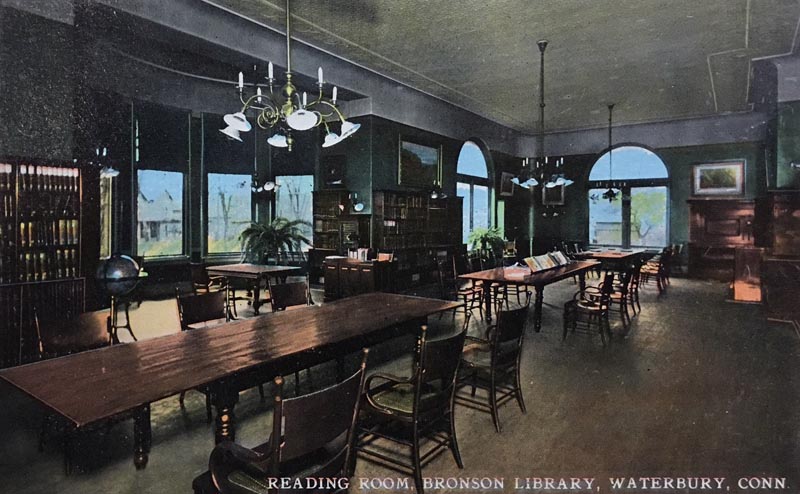

Bassett oversaw two major building projects. The first, in 1883, involved the construction of an addition to the back of the library to make room for more books and to enlarge the reading rooms. The second, more ambitious project, was the construction of an entirely new building on Grand Street in 1894. The new library, designed in the Italian Renaissance Revival style, consisted of two sections: a palazzo-style main building with reading rooms and offices, and a more utilitarian rear building for the book stacks, which was able to hold up to 220,000 volumes.

The interior of the building featured a large entry hall with a central staircase and an impressive marble fireplace. A second marble fireplace was located in the general reading room. A smaller reading room was available for women. The second floor housed the law, science, government, and fine arts reference rooms. The third floor rooms were used to exhibit natural history collections and art. The library’s collections quickly expanded to include minerals, rocks, seashells, dried plant specimens, and Civil War relics collected on battlefields.

Homer Bassett ran the Silas Bronson Library for three decades, overseeing tremendous changes to Waterbury’s public library. Public libraries in general were changing by the turn of the century, expanding their holdings to encompass more than just books. As Bassett himself commented during the 1890s, “It will be seen that the Library is not merely a collection of books but in common with many others has drifted away from the old idea and the addition of collections of various kinds of objects are being made that greatly increase its usefulness.”

|